What I am about to say is going to sound crazy to a lot of people. You may stop reading and never come back. But, I encourage you, stick with it. Keep an open mind. Don’t use errors to measure defensive performance.

Get outta here, right?? What is this world coming to? It’s society today, I tell you! Everyone gets a trophy! No one has to feel bad for getting an error!

There is a long list of reasons to forget all about this metric. The bottom line is simple:

- How much value does it provide?

- Can you get more insight by removing it and focusing on other metrics?

The “error” metric is one of those stats that we use because it’s what we’ve always used. Granted, we’ve become far more sophisticated when it comes to measuring defensive proficiency at the highest levels, but even there errors are tracked.

If you’re open to questioning its value, you may see what I see: The defensive error is one of the most worthless, problematic stats in all of baseball.

Not only is the error deeply flawed in terms of expressing anything of value, but it’s also the source of contention and drama on youth baseball teams. But, what do you expect? It’s a subjective stat meant to assign blame for something bad that happened. Very little good can come of it.

But, let’s brush aside the emotion here and provide some specific examples of why it’s so flawed. After that, we’ll discuss what you can use instead to measure defensive proficiency.

Why the Defensive Error is Flawed

First, the obvious: Scoring errors is subjective.

How or whether an error is called could be influenced by who was involved in the play, who was on the mound, and who the scorekeeper was. We know this is the truth. And sometimes it’s the opposite of what you’d expect — a scorekeeper may be tougher on their own child.

Being easier or tougher on anyone doesn’t make it okay. It just makes it more obvious that this metric is flawed.

Second, in order to make an error, you must first do several things right.

You need to be properly positioned. You need to get a good jump on the ball. You need to have quickness and good footwork.

If you’re able to get to the ball, you can then drop it, boot it, or throw it away. If your range is so bad that you never get to a ball, you’ll almost never make an error.

The best fielders will have the most opportunities to make errors because they put themselves into the best position to either make a good or bad play.

Third, the execution of a single play — and the failure to do so — is a team effort.

It’s funny, I was just watching a Little League World Series play and I immediately thought of this. The shortstop made an incredible play. He then made a difficult, but slightly inaccurate, throw to first. The first baseman, luckily, scooped the ball and helped record the out. Everyone raved about the amazing play the shortstop had made. But if that ball got by the first baseman, that runner not only reaches, but he advances to second. The shortstop would have been issued an error.

This kind of thing happens all the time. Teammates help each other execute a play. They also can be the reason why someone else was or wasn’t assigned an error by making an above-average play themselves, backing up the play, or hustling.

A player can do the exact same thing in two different plays, but due to their teammate, they can get different results. That’s what makes this a team play and a team metric.

But What About Obvious Errors?

I can hear you screaming this through the computer screen.

An easy ground ball right to the third baseman. Through his legs.

A popup right to the shortstop. Dropped.

An easy grounder to the shortstop. Plenty of time. Airmails it over the first baseman’s head.

I understand. It’s perfectly obvious whose fault it was. But… why does it matter so much??

The player who made the obvious mistake isn’t getting away with anything by not recording an error. If you focus on positive metrics instead of negative, there won’t be a positive play recorded either.

That takes us here…

What to Measure Instead

So, even if you agree with everything I’ve written here so far, you may be thinking: “Fine, but this is what we’ve got. What should we measure instead?”

I’m glad you asked. Honestly, what I’m about to tell you is why recording the error at all — at least for measuring defensive proficiency — just isn’t necessary.

The error measures how many mistakes someone made (subjectively and in theory). Fielding percentage could attempt to measure what percentage of plays you made cleanly that you were supposed to make.

But, both metrics miss a very important point that we all should care about: Who made the most plays? Who executed the most outs?

Even if you don’t record the obvious errors, as mentioned above, you aren’t recording an out either. So, the fielder isn’t “getting away” with anything. You will still want to compare players, and one way to do that is by comparing successful execution.

Imagine, if you will, a hypothetical situation where both Tommy and Jimmy are shortstops.

In one game, Tommy catches a pop-up (putout) and throws out a runner on a grounder (assist). He makes no errors.

In the next game, Jimmy catches two pop-ups and throws out three runners on grounders. He also throws a ball away on a ball he gets to, resulting in a scored error.

Tommy made 100% of his plays. He didn’t make an error. Jimmy executed five outs. But he also made an error.

I know, I know. Small sample size! Go ahead. Repeat it for 10 games. Multiply it by 10. Tommy doesn’t make mistakes. His range sucks. Jimmy makes a few. But he gets to a lot more balls. And, most importantly, he executes more outs.

What do you want more? Do you want the player who hasn’t made mistakes? Or do you want the player who has executed more outs?

You may think this is completely hypothetical and will never happen, but it happens on a small scale all the time. Baseball is a game of outs. The team that can convert the most outs of their opportunities is the team that will have the best chance to win.

Does making an error mean that a player didn’t execute an out? SURE! But there are so many factors at play with those errors. Were these groundballs or popups that Jimmy never would’ve got to anyway? Are they difficult throws that a weak first baseman couldn’t receive?

Give me the player who executes a large volume of outs all day. That means getting to more baseballs (good range) and execution.

Of course, the one issue is that you can’t just compare the number of outs converted in a vacuum. Catchers and first basemen will make the post putouts. Infielders will make more assists (and probably outs generally) than outfielders.

You’ll need a way to compare this by position. This isn’t possible with Gamechanger. You’ll either need to use an app that can handle this or you’ll need to assign someone who keeps track of these things.

We used iScore for official scoring. It allows us to break down innings, assists, and putouts by position. I can then compare players’ defensive performance when they were playing the same position.

Here’s an example…

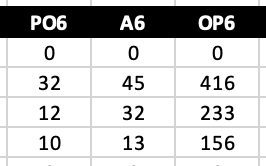

The OP6 column is the number of outs played at shortstop (so, three outs would be a full inning). You can then compare these players based on the number of total outs they’ve converted.

What About Pitchers?

One of the questions that come about removing errors almost always comes from concerned parents of pitchers: But, that player made an error, and some of those runs were UNEARNED!

I find this argument laughable. Baseball is a team sport. Just because a defensive mistake was made with two outs doesn’t mean that the pitcher is no longer responsible for anything that happens after.

If your only metric to evaluate pitchers is ERA, you’re missing the point. The pitcher can’t do anything about where a ball is hit or whether someone fields it. His focus is on throwing strikes and getting weak contact. Measure things associated with that.

Of course, this requires an adjustment of thinking and expectations. Youth fielders are far from perfect. The more balls that are hit in play, the more mistakes are likely to happen. The best way to avoid this: Strikeouts.

Yes, pitching to contact has value, too, and you should trust your defense. But mistakes in the field are going to happen. And the strikeout pitcher is going to see less of those than the contact pitcher.

Ultimately, the Earned Run Average will go up for everyone if you take this approach. But it also isn’t all that valuable of a stat, at least for evaluating a pitcher — it’s more of a team metric when he’s on the mound. Other stats like strike percentage, weak hit percentage, and strikeouts vs. walks are FAR more valuable for predicting performance.

If you’re a parent who is constantly freaking out about earned and unearned runs, you’re part of the problem here. Just let it go — we don’t need to assign blame for that run scoring. Your son’s ERA will be higher, but no scout is looking at that.

Your Turn

Look, I understand removing the error from scoring is a huge adjustment. It feels wrong because it’s something we’ve always done. It’s a big part of our language when discussing baseball.

But overall, this is a much HEALTHIER way of looking at defensive performance. Trash the error and you no longer need to worry about the drama that all-too-often follows the subjective assigning of blame.

But, it’s far more than that. Once you get rid of the stat and start focusing on things that actually matter, you’ll wonder why you cared so much about the Error stat in the first place.

I’d love to hear your thoughts! Let me know in the comments below.